Life on Mars: Why All the Skipping?

Defying Gravity . . . and Darwin

***Note About the “Life on Mars” Series: When people learn that I have nine children, I get a lot of questions. One of them is “Are you from Mars?” This essay is part of the “Life on Mars” series that dives into elements of raising a family of unusual size (by today’s standards. A family of nine used to be no big deal). The first entry—on the Marital Art of Pew Jitsu—can be found here End of Note***

I am afraid to say it for fear that the powers that be will realize their oversight and it will no longer be true. But I am going to say it anyway.

There are no Olympic competitions for skipping.

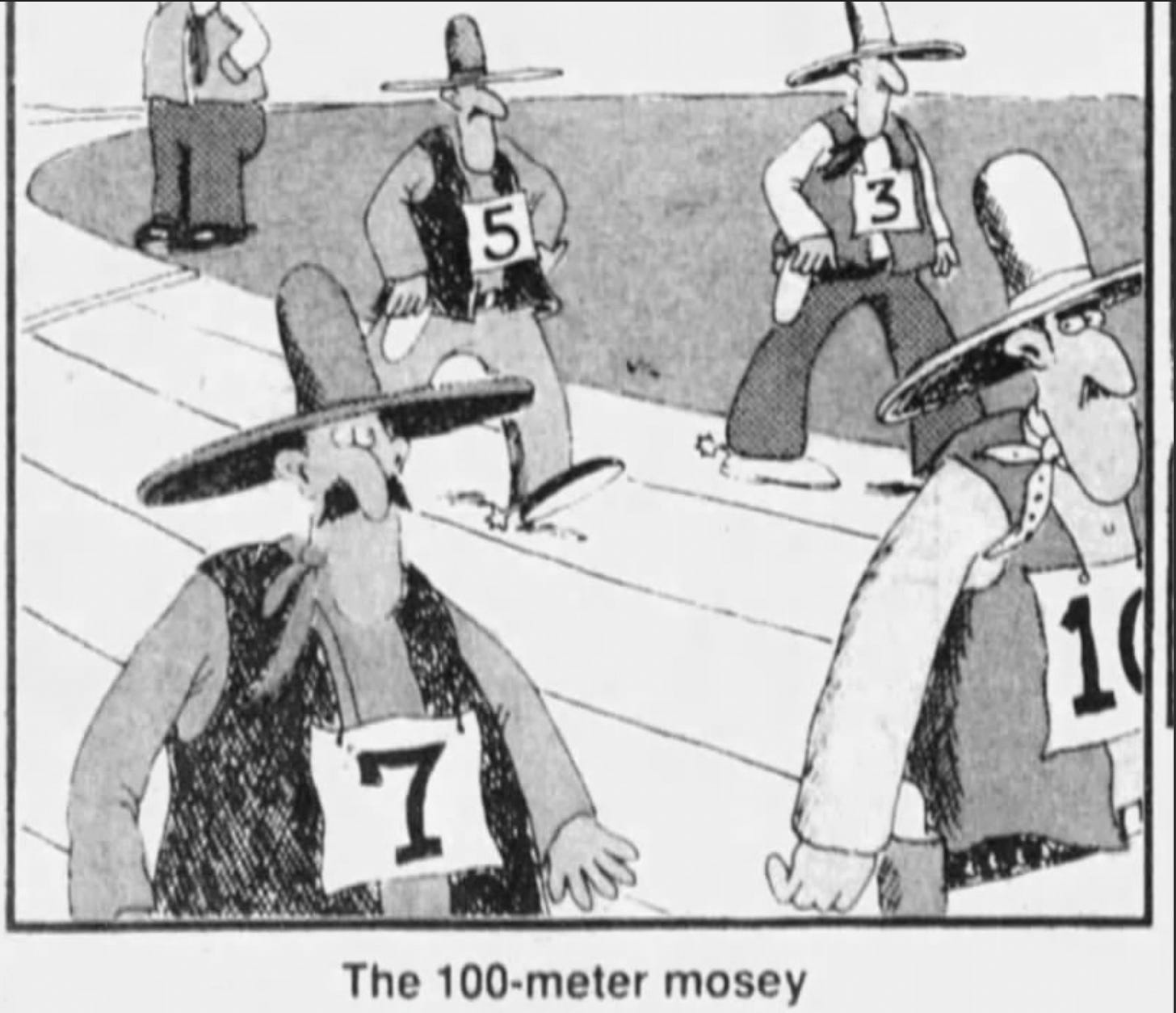

There is Olympic ski jumping, speed skating, ice dancing, break dancing, and even, speed walking (not that there’s anything wrong with that). I can only assume this last one was inspired by Gary Larson’s Far Side about the 100-meter mosey.

There is no elite competition for skipping. No speed skipping. No long distance skipping. No 100-meter freestyle skipping. But skipping is a fundamental element of human motion. Every child skips. Dissertations, studies, articles, and school readiness policies (ugh) are written because of that truth.

As a dad of nine children, I have seen it first hand, so I have pondered the question myself, “Why all the skipping?” I have never been asked, “How did you teach all your children to skip?” It isn’t something you teach.

A younger daughter may look on as an older child skips by and her eyes will say, “What was THAT?!” No one had informed her she was part of a species with the capacity for flight. Most children get basic instruction:

Step.

Hop.

Step with the other foot.

Hop.

First attempts feel like reading those lines. Awkward and slow.

—Step. Look around. Jump.

—What? Step. Stamp.

—Jump.

—STOMP.

But then something happens. At different ages for different children, it clicks. She gets it and takes flight herself. At that moment, skipping will become the dominant form of transportation.

Both boys and girls skip, but we must face the facts. Boys and and girls are different and it is the girls who dive deep into the craft and stick with it the longest. In fact, it may be that the height of skipping mastery is only ever achieved by the six year old girl.

The act itself is simple, but when mastered takes on the character of artistry, a series of movements that defy gravity, tiny feats of acrobatics performed without a net.

Some advanced skipping techniques swing the back (hop) leg from the left to the right and then the next goes from right to left, creating a swaying zig zag. If examined in slow motion, we would see the skipper is teetering on the edge of total collapse on each leap. When observed at full speed, however, we see a swinging hand-bell transformed and bounding bird.

Other times, the hop leg might be kept at a low altitude and pulled forward in shuffle-hop with an overall back leaning posture, an improbable reverse moon-walk with dramatic knee pulled toward the sky.

Arms will swing together in time, or sometimes alternate, sometimes with hands reaching toward the sky. Sometimes fists are double clutched toward the chin, a gesture of hope and anticipation in order to maximize the vertical. Sometimes the arms don’t move at all, but are held out wide like wings.

Most of the permutations of the skip are also executed in a classic and incongruous pairing with an older, slower, non-skipping adult—usually a dad. With a hand stretched upward and anchored to a six foot tall man with a normal stride, the repertoire of skip-skills unfold down sidewalks, across beaches, over fields, and, most frequently, through Home Depot parking lots on the way to get plumbing supplies. Were there an olympic event for skipping, this would be the maneuver with highest difficulty rating. Don’t get ahead or fall behind and above all, don’t stop skipping. Execute all the aeronautics you have learned while tethered to a slow moving obstacle. Ten out of ten for difficulty.

After some years of practice, a dad can assist by sensing the downward pressure as the skipper is about to descend and can add lift, elevating the arm at the right moment, achieving greater height and flying the skipper over the space that would have been the next skip, and lower her down in time for the one after that. If there were a panel of judges they would give bonus points to the dad who keeps a straight face as these antics unfold.

The tough techniques of skipping are never taught, however. No coaches. No early morning hours at the skip-gym. No AAU teams. No clinics or skip-camps. This wild variety of techniques gets absorbed, invented, and re-invented by each child—on the fly.

In the “Mastery of Flight” episode of the nature documentary, Life of Birds, David Attenborough appears high above a mountain range in a piloted glider near griffin vultures in flight. As they observe the creatures soaring on the thermal updrafts, diving and swooping in slow beautiful curves, the pilot indicates that the birds perform their antics “just for fun.” Attenborough is taken aback and laughs. The idea conflicts with his commitment to draw every animal action back to Darwinian necessity. He laughs, yet he seems to concede the point offered by the pilot, “these birds can’t see a mouse from 15,000 feet.”

Attenborough would have to conclude the same about skipping. “We see here a young female has just mastered the technique called, ‘skipping’ and will proceed to carry out this activity, circling the yard in a manner that simply expends energy with no discernible purpose whatsoever, and she seems unaware of potential threats not only from falling but from her big brothers playing football in the same yard.”

Michael Behe, author of Darwin’s Black Box advances compelling scientific arguments against the Darwinian theory of evolution based in-part on the idea of “irreducible complexity.” The idea that at the most basic level, there are such complex structures and processes in biological life, that a random mutation could never have produced them. One small deviation, a micro mutation, could not have produced the outboard motor on the back of a primordial paramecium. One wrong move and the whole system would collapse. He could reach a similar conclusion observing a six year old ripping off her favorite skipping maneuver. Call it inexplicable levity.

I suspect there are lost notebooks from Charles Darwin himself where he wrestled with problems like these.

His draft treatise, What is it with all the skipping? will be compelling reading when it is finally found. Perhaps it will be found underneath his other lost volume on the eating habits of toddlers, Survival of the Obstinate.

Skipping serves no Darwinian purpose. It is just beauty and joy in service to no particular end. The six year old girl seems to delight in defying gravity and has no idea she may also be defying Darwin.